Ewa Doroszenko, Jacek Doroszenko

Intermedialna wystawa duetu Ewy Doroszenko i Jacka Doroszenko składa się z serii fotografii, unikatowych obiektów fotograficznych, instalacji dźwiękowej oraz prac wideo, realizowanych w ciągu ostatnich lat w ramach programów Artist-in-Residence w Norwegii, Grecji, Litwie, Czechach, Hiszpanii oraz Portugalii. Tematem łączącym wszystkie prace jest zakrzywienie postrzegania krajobrazu naturalnego oraz pytania o przesuwające się granice między domenami natury i technologii.

Nasz stosunek do krajobrazu jest złożony i pełen sprzeczności. Łakniemy kontaktu z przyrodą dziewiczą, prawdziwą, nienaruszoną przez człowieka, tymczasem nie potrafimy oprzeć się pokusie poprawiania tego, z czym się stykami. Kapitan James Cook ponoć zakładał ogrody w stylu angielskim (a więc ogrody naśladujące dziką przyrodę) na każdej wyspie południowego Pacyfiku, do jakiej dobijał podczas swoich podróży pod koniec XVIII stulecia. Natrafiał na obszary prawdziwie nietknięte, lecz starał się je uczynić jeszcze bardziej „naturalnymi”, ale w zgodzie z własnymi przekonaniami o tym, jak przyroda wyglądać powinna.

Również dzisiaj, w dobie nadprodukcji fotografii, doświadczamy krajobrazu w sposób zapośredniczony. Widzimy zawsze tylko to, w co wierzymy (aby zacytować tytuł świetnej książki Errola Morrisa poświęconej fotografii). W „Niemożliwym horyzoncie” Ewa i Jacek Doroszenko ukazują najbardziej zaskakujący paradoks krajobrazu: fakt, że krajobraz jako taki nie istnieje. To, co istnieje, to punkty obserwacyjne, punkty patrzenia. Krajobraz jest w istocie swojej przeniesieniem w dwa wymiary tego, co istnieje w świecie trójwymiarowym. Gdy myślimy o Wielkim Kanionie, wodospadzie Iguaçu, fiordach Norwegii czy ergach Sahary, nieuchronnie pamięć przywołuje nam konkretne zdjęcia wykonane z konkretnych miejsc o konkretnych porach.

Ewa i Jacek Doroszenko prowadzą grę z pojęciem krajobrazu, podejmując coraz to inne jego aspekty. Punktem wyjścia stanowią dla nich słowa polskiego logika Alfreda Korzybskiego: mapa to nie terytorium. Jorge Luis Borges pisał: „W owym Cesarstwie Sztuka Kartografii osiągnęła taką doskonałość, że Mapa jednej tylko Prowincji zajmowała całe Miasto, a Mapa Cesarstwa całą prowincję. Z czasem te Niezmierne Mapy okazały się już niezadawalające i Kolegia Kartografów sporządziły Mapę Cesarstwa, która posiadała Rozmiar Cesarstwa i pokrywała się z nim w każdym Punkcie. Mniej Oddane Studiom Kartografii Następne Pokolenia doszły do wniosku, że ta obszerna Mapa jest Nieużyteczna i nie bez Bezbożności oddały ją na Pastwę Słońca i Zim. Na Pustyniach Zachodu zachowały się rozczłonkowane Ruiny Mapy.”

Cesarstwo z opowiadania „O ścisłości w nauce” było, rzecz jasna, zmyślone. Nie są wszelako zmyślone zdjęcia satelitarne w mapach Google’a, które na pozór coraz precyzyjniej zaczynają się pokrywać z terytorium, lecz oferują doświadczenie krajobrazu w sposób rozczłonkowany, niejako nieciągły, pozbawiony struktury. Nieciągłość, przerwanie spójności, dekonstrukcja struktury są też tym, czego dokonuje duet Doroszenko w swoich kolażach, obiektach, instalacjach i renderach cyfrowych. Estetyka glitchu i generatywnej niedoskonałości wpisana zostaje w długą tradycję myślenia o krajobrazie jako pewnym fantazmacie, dla którego kategoriami organizacyjnymi są wzniosłość i malowniczość, a które do dziś kształtują nasze oczekiwania i wyobrażania o obcowaniu z naturą.

Korzystając z popularnych gier komputerowych, przewodników turystycznych i innych internetowych źródeł, artyści ujawniają bardzo powszechne w epoce cyfrowej marzenia o odpoczynku w idyllicznym krajobrazie. Przyglądają się różnorodnym krajobrazom w oparciu nie tylko o wizualne aspekty rzeczywistości, ale w równym stopniu artyści eksplorują pomijane zazwyczaj otoczenie dźwiękowe. W filmach prezentowanych na wystawie Ewa i Jacek Doroszenko wykorzystują nagrania terenowe jako podstawę polifonicznych kompozycji dźwiękowych, wprowadzają także działanie performatywne umożliwiające wykorzystanie walorów naturalnych krajobrazów jako systemów notacji muzycznej. W instalacji dźwiękowej prezentują sposoby muzycznego odczytywania rytmiki zredukowanego otoczenia dźwiękowego poprzez wzbudzanie i preparację materiałów syntetycznych.

Krzysztof Miękus

The intermedia exhibition by duo Ewa Doroszenko and Jacek Doroszenko consists of a series of photographs, unique photographic objects, a sound installation, and video works, realized over the past years as part of Artist-in-Residence programs in Norway, Greece, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Spain, and Portugal. The unifying theme binding of all the works is the curving perception of the natural landscape and questions about the shifting boundaries between the domains of nature and technology.

Our relationship with landscapes is intricate and contradictory. We yearn for contact with pristine, untouched nature, yet we cannot resist the temptation to alter what we encounter. Captain James Cook reportedly established English-style gardens (thus, gardens imitating wild nature) on every island he reached in the South Pacific during his late 18th-century voyages. While encountering genuinely untouched areas, he sought to make them even more “natural,” but in accordance with his own beliefs about how nature should appear.

Even today, in the era of photographic overproduction, we experience landscapes in a mediated manner. We always see only what we believe (to quote the title of Errol Morris’s excellent book on photography). In “The Impossible Horizon,” Ewa and Jacek Doroszenko reveal the most surprising paradox of the landscape: the fact that the landscape as such does not exist. What exists are vantage points. The landscape is essentially a two-dimensional representation of what exists in the three-dimensional world. When we think of the Grand Canyon, the Iguazu Falls, the fjords of Norway, or the ergs of the Sahara, our memory inevitably recalls specific photographs taken from specific places at specific times.

Ewa and Jacek Doroszenko engage in a game with the concept of the landscape, addressing its various aspects. Their starting point is the words of Polish logician Alfred Korzybski: the map is not the territory. Jorge Luis Borges wrote: “In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map.” The Empire from the story “On Exactitude in Science” was, of course, fictional. However, the satellite images in Google Maps are not fictional – they seem to increasingly accurately overlap with the territory, but they offer an experience of the landscape in a fragmented, discontinuous, and structureless manner. Discontinuity, interruption of coherence, and deconstruction of structure are also what the Doroszenko duo accomplishes in their collages, objects, installations, and digital renders. The aesthetics of glitch and generative imperfection are inscribed in the long tradition of thinking about the landscape as a phantasm, for which the organizational categories are sublimity and picturesque, which still shape our expectations and imaginings of engaging with nature.

Using popular computer games, travel guides and other online sources, the artists reveal the dream of relaxing in an idyllic landscape, which is very common in the digital age. They look at a variety of landscapes based not only on visual aspects of reality, but equally the artists explore the usually overlooked sound environment. In the films presented at the exhibition, Ewa and Jacek Doroszenko use field recordings as the basis for polyphonic sound compositions and introduce a performative action that allows them to use the qualities of natural landscapes as systems of musical notation. In the sound installation, they present ways of musically reading the rhythmics of the reduced sound environment through the excitation and preparation of synthetic materials.

Ewa Doroszenko

Ghost Island (2023), How to Travel (2019)

obiekty fotograficzne: drewno, fotografie na papierze, pianka poliuretanowa, szpilki | 50 x 50 x 7 cm każda z prac

Ewa Doroszenko wychowała się w rodzinie tradycyjnych fotografów. Dorastając, miała okazję obserwować przemiany, jakich przysporzyło rzemiosłu fotograficznemu pojawienie się fotografii cyfrowej. Relacja artystki z obrazami fotograficznymi prawdopodobnie była zupełnie odmienna od doświadczeń jej rówieśników. Odpady fotograficzne wykorzystywała w zabawach, a analogowe próbki służyły jej jako podkład do rysowania. O fotografii myślała nie tylko w kontekście technologii czy medium, które wpływa na sposób postrzegania rzeczywistości, ale przede wszystkim jako o obiekcie. Te refleksje miały wpływ na późniejszą twórczość artystki, m.in. na proces postawania cyklów obiektów fotograficznych Ghost Island oraz How to Travel. Obiekty powstały przy użyciu analogowych technik fotograficznych i rzeźbiarskich oraz technik cyfrowych. Artystka zbudowała trójwymiarowe reprezentacje nieistniejących pejzaży z fragmentów druków i odbitek fotograficznych różnorodnych przyrodniczo cennych miejsc na świecie, którym zagraża ekspansywna działalność człowieka.

Ewa Doroszenko grew up in a family of traditional photographers. Growing up, she had the opportunity to observe the changes brought about to the photographic craft by the advent of digital photography. The artist’s relationship with photographic images was probably quite different from the experience of her peers. She used photographic waste in play, and used analogue samples as backgrounds for her drawings. She thought of photography not only in terms of a technology or a medium that influences the way she perceives reality, but primarily as an object. These reflections influenced the artist’s later work, including the process of putting up the photographic object series Ghost Island and How to Travel. The objects were created using analogue photographic and sculptural techniques as well as digital techniques. The artist constructed three-dimensional representations of non-existent landscapes from fragments of prints and photographic prints of a variety of naturally valuable places around the world that are threatened by expansive human activity.

Ewa Doroszenko

Phantom Territory (2019)

Instalacja fotograficzna: pianka poliuretanowa, fotografie na papierze, szpilki, stalowy stelaż | 121 x 33 x 28 cm

Praca Phantom Territory powstała przy użyciu analogowych technik fotograficznych i rzeźbiarskich oraz współczesnych technik cyfrowych. Artystka zbudowała trójwymiarową reprezentację nieistniejącej góry z fragmentów druków i odbitek fotograficznych pochodzących z Google Street View, popularnych gier komputerowych, przewodników turystycznych i innych internetowych źródeł. Opierając się na obserwacjach naturalnego krajobrazu, który w dzisiejszych czasach jest częściej uwieczniany na fotografiach niż bezpośrednio doświadczany, Ewa Doroszenko stara się zakwestionować zaufanie do cyfrowo skonstruowanych obrazów. Informacyjna rzeczywistość nie tylko umożliwia lepsze poznanie świata, ale zmienia nasz sposób widzenia, wpływa na procesy poznawcze i modyfikuje nasze wyobrażenia o tym, czym jest naturalny krajobraz.

The Phantom Territory project was created using analogue photographic and sculptural techniques and contemporary digital techniques. The artist has constructed a three-dimensional representation of a non-existent mountain from print fragments and photographic prints sourced from Google Street View, popular computer games, travel guides and other online sources. Drawing on observations of the natural landscape, which these days is more often captured in photographs than directly experienced, Ewa Doroszenko seeks to question trust in digitally constructed images. Informational reality not only enables us to know the world better, but it changes our way of seeing, influences our cognitive processes and modifies our ideas of what a natural landscape is.

Ewa Doroszenko

Impossible Horizon (2019)

Instalacja fotograficzna: pianka poliuretanowa, fotografie na papierze, szpilki, stalowy stelaż | 121 x 33 x 29 cm

Współczesna kultura staje się coraz bardziej kulturą strumienia cyfrowych informacji, w której podział na wirtualne i realne jest coraz mniej aktualny. Informacyjna rzeczywistość nie tylko umożliwia lepsze poznanie świata, ale zmienia nasz sposób widzenia, wpływa na procesy poznawcze i modyfikuje nasze wyobrażenia o tym, czym jest naturalny krajobraz. Praca Impossible Horizon powstała przy użyciu analogowych technik fotograficznych i rzeźbiarskich oraz współczesnych technik cyfrowych. Z wydrukowanych fragmentów zrzutów ekranu pochodzących z wyjątkowo brutalnych gier komputerowych Ewa Doroszenko zbudowała trójwymiarową reprezentację nieistniejącej góry.

Contemporary culture is increasingly becoming a culture of digital information streams, in which the division between virtual and real is less and less valid. Informational reality not only makes it possible to know the world better, it changes the way we see, influences our cognitive processes and modifies our ideas of what the natural landscape is. The work Impossible Horizon was created using analogue photographic and sculptural techniques and contemporary digital techniques. From printed fragments of screenshots from extremely violent computer games, Ewa Doroszenko built a three-dimensional representation of a non-existent mountain.

Ewa Doroszenko

Overlooked Horizons (2023)

Cykl wielkoformatowych druków poliestrowych, 400 × 100 cm każdy, edycja: 1/2 edycja + 1 AP

Nadmiar wizualnych bodźców we współczesnej rzeczywistości sprawia, że stajemy się coraz mniej wrażliwi na nasze otoczenie, w tym, na zanikający krajobraz naturalny. W tytule cyklu pojawia się termin horyzont, rozumiany nie tylko jako linia styku nieba z powierzchnią ziemi, ale przede wszystkim jako zasięg lub granica naszych możliwości percepcyjnych w dobie przeładowania informacyjnego. Tematem cyklu Overlooked Horizons jest zakłócenie postrzegania krajobrazu oraz pytania o przesuwające się granice między domenami natury i technologii. Prezentowane na wystawie wielkoformatowe druki fotograficzne powstały ze zgromadzonych przez artystkę fotograficznych widoków – niewykorzystanych resztek fotograficznych, które artystka, w procesie selekcji, odrzuciła realizując projekty w ramach międzynarodowych programów Artist-in-Residence, m.in. w Kunstnarhuset Messen Ålvik (Norwegia), Klaipeda Culture Communication Center (Litwa), The Island Resignified Lefkada (Grecja) i Pragovka Gallery (Czechy). Przeoczone, pierwotnie niedostrzeżone lub uznane za nieatrakcyjne pejzaże, zwróciły uwagę artystki na jej własne ograniczające oczekiwania od kontaktu z naturalnym krajobrazem.

The overabundance of visual stimuli in contemporary reality is making us less and less sensitive to our surroundings, including, the disappearing natural landscape. The term horizon appears in the title of the series, understood not only as the line of contact between the sky and the earth’s surface, but above all as the extent or limit of our perceptual possibilities in an age of information overload. The theme of the Overlooked Horizons series is the disruption of landscape perception and questions about the shifting boundaries between the domains of nature and technology. The large-format photographic prints presented in the exhibition were created from the artist’s accumulated photographic views – unused photographic remnants that the artist, in the process of selection, discarded while realising projects within the framework of international Artist-in-Residence programmes, including at Kunstnarhuset Messen Ålvik (Norway), Klaipeda Culture Communication Center (Lithuania), The Island Resignified Lefkada (Greece) and Pragovka Gallery (Czech Republic). Overlooked, originally overlooked or considered unattractive, the landscapes have drawn the artist’s attention to her own limiting expectations from contact with the natural landscape.

Ewa Doroszenko

Impossible Territory (2019)

Cykl fotografii (druk atramentowy na papierze fotograficznym FOMEI Collection Velvet 265 gsm), 70 x 50 cm każda z prac, edycja: 2/5+ 1AP

Ewa Doroszenko tworzy obrazy fotograficzne wykorzystując analogowe techniki fotograficzne i rzeźbiarskie oraz techniki cyfrowe. Z fragmentów druków i odbitek fotograficznych buduje wielkoformatowe trójwymiarowe kolaże, a następnie fotografuje je. Powstałe widoki modyfikuje na ekranie komputera poprzez wielokrotne interwencje. To wieloetapowe działanie doprowadza do sytuacji, w której trudno jest rozpoznać, która część fotograficznego obrazu została stworzona analogowo, a która wskutek cyfrowej ingerencji. Cykl odnosi się do reprezentacji naturalnego pejzażu oraz funkcji współczesnej fotografii, która odgrywa szczególną rolę w budowaniu iluzorycznych wizji krajobrazu. Jak pisała Susan Sontag, Potęga fotografii doprowadziła do deplatonizacji naszego rozumienia świata, sprawiając, że coraz mniej prawdopodobna jest refleksja nad naszym doświadczeniem oparta na rozróżnieniu między obrazami a przedmiotami rzeczywistymi, kopiami a oryginałami.

Ewa Doroszenko creates photographic images using analogue photographic and sculptural techniques as well as digital techniques. She builds large-scale three-dimensional collages from fragments of prints and photographic prints and then photographs them. He modifies the resulting views on the computer screen through multiple interventions. This multi-stage operation leads to a situation where it is difficult to recognise which part of the photographic image has been created analogue and which part has been created by digital interference. The series refers to the representation of the natural landscape and the function of contemporary photography, which plays a special role in constructing illusory visions of the landscape. As Susan Sontag has written, The power of photography has led to a deplatonisation of our understanding of the world, making it increasingly unlikely to reflect on our experience based on the distinction between images and real objects, copies and originals.

Jacek Doroszenko

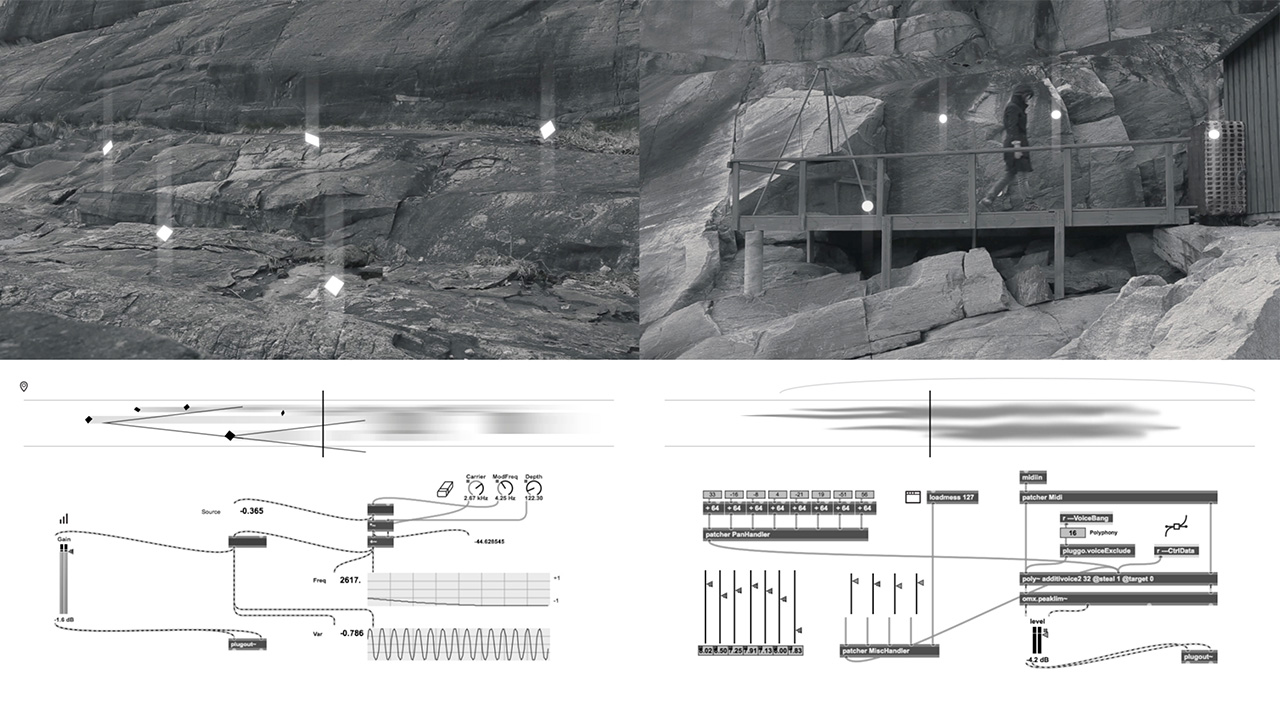

It is hard to find a polyphonic body (2016)

Wideo, 07’45”, 4K, edycja: 2/4 + 1 AP

Film został zrealizowany w ramach programu Artist-in-Residence w Kunstnarhuset Messen Ålvik w Norwegii. Konstrukcja filmu opiera się na wykorzystaniu krajobrazu jako przestrzeni notacji muzycznej. Okolice majestatycznych fiordów zostały zaadaptowane jako środowisko do stworzenia unikalnej partytury utworu wykonywanego w tym samym czasie przez zestaw instrumentów wirtualnych. Niewystarczający, standardowy zapis nutowy został zastąpiony wizualnym kodem o performatywnym charakterze. Przemieszczająca się postać determinuje elementy kompozycji muzycznej, jej położenie wpływa na zmiany wysokości dźwięku w skali opartej na częstotliwości.

The video has been produced as part of the Artist-in-Residence programme at Kunstnarhuset Messen Ålvik in Norway. The construction of the film is based on the use of landscape as a space for musical notation. The surroundings of the majestic fjords were adapted as an environment to create a unique score of a piece performed at the same time by a set of virtual instruments. The inadequate standard musical notation has been replaced by a visual code of a performative nature. The moving figure determines elements of the musical composition, its position influencing pitch changes in a frequency-based scale.

Jacek Doroszenko, Ewa Doroszenko

Pulse of the Last Ecotones (2024)

instalacja dźwiękowa, druki na materiale, elementy aluminiowe, części elektroniczne, przewody, stalowe stelaże, cewki elektromagnetyczne, preparowane wzbudniki dźwiękowe, blacha, ścieżka dźwiękowa, 210 × 510 × 300 cm

Tytuł pracy odnosi się do pojęcia ekotonu, w ekologii oznaczającego strefę przejściową między dwoma lub kilkoma różnymi sąsiadującymi ekosystemami, w której współistnieją organizmy sąsiadujących biocenoz. Typowe ekotony obejmują krawędzie lasów lub strefy brzegowe. Strefa przejściowa nazywana jest również granicą ekologiczną, strefą nadbrzeżną, strefą buforową, granicą, krawędzią, przejściem biotycznym. Ekotony, które na ogół są zredukowane do jednej linii na mapach, mają bogate cechy ekologiczne, m.in. charakteryzują się zwiększoną różnorodnością biologiczną. Postępująca ekspansja terytorialna człowieka spowodowała powstanie antropogenicznych granic i sukcesywne wypieranie wielu stref styku. W tej poetyckiej realizacji prosty perkusyjny rudiment, wykonywany przez cewki elektromagnetyczne, odbija się zniekształconym pulsującym echem i wybrzmiewa jako transmisja emitowana przez blaszane „głośniki”, jednocześnie stanowiące barierę emisji. W kontrze do hałaśliwie rozpędzonej cywilizacji, artyści proponują uważne nasłuchiwanie otoczenia dźwiękowego, które zazwyczaj traktowane jest jedynie jako tło, swoiste uzupełnienie tego, co widać.

The title of the installation refers to the concept of an ecotone, in ecology denoting a transitional zone between two or more different neighbouring ecosystems in which organisms of neighbouring biocoenoses coexist. Typical ecotones include forest edges or riparian zones. A transition zone is also called an ecological boundary, riparian zone, buffer zone, border, edge, biotic transition. Ecotones, which are generally reduced to a single line on maps, have rich ecological characteristics, including increased biodiversity. The progressive territorial expansion of humans has resulted in the creation of anthropogenic boundaries and the successive displacement of many interface zones. In this poetic realisation, a simple percussive rudiment, performed by electromagnetic coils, reverberates with a distorted pulsating echo and resounds as a transmission emitted by tin “loudspeakers”, at the same time constituting a barrier to emission. As a counterpoint to the noisy rush of civilisation, the artists propose an attentive listening to the sound environment, which is usually only treated as a background, a kind of supplement to what can be seen.

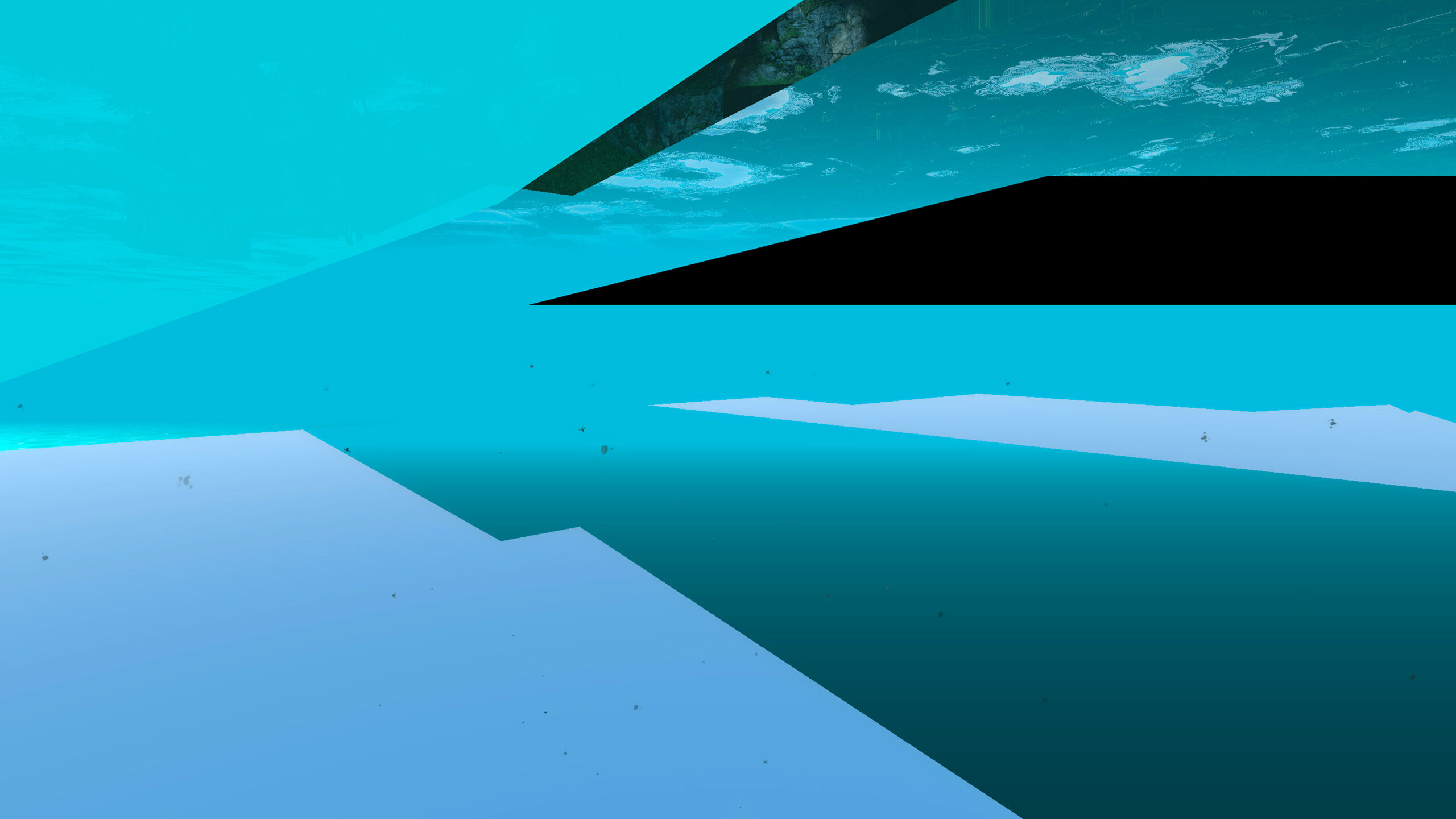

Ewa Doroszenko

Imagine yourself on an island in the middle of the ocean (2018)

Wideo, 07’50”, Full HD, edycja: 3/5 + 1AP

Zainspirowana popularnymi na kanale YouTube medytacjami online, Ewa Doroszenko prezentuje jeden ze sposobów, w jaki próbujemy osiągnąć stan wewnętrznej równowagi w dobie przeładowania informacyjnego. Wideo powstało w oparciu o wirtualne krajobrazy oraz cyfrowe zniekształcenia. Wykorzystując alfabet współczesności i sięgając po jeden z najbardziej klasycznych tematów – pejzaż, Ewa Doroszenko ujawnia bardzo powszechną w epoce cyfrowej tęsknotę za relaksem w idyllicznym krajobrazie. Film powstał w oparciu o refleksje artystki towarzyszące pobytom twórczym w ramach programów Artist-in-Residence na wyspie Lefkada w Grecji i Azorach w Portugalii. Muzykę do filmu skomponował Jacek Doroszenko.